Between mark and script: reading ambiguity

Research question: If drawing and writing demarcate a continuum, what factors influence our perception of work that inhabits the liminal area bracketed by the polarity of writing and picturing, text and image, script and mark?

Abstract: Many interesting and relevant examples non-Western examples of work that falls in an ambiguous area between drawing and writing exist, but those used in this study have been produced in Europe and America. Calligraphy seems an obvious example but falls outside this ambiguous area. The terminology to discuss writing, especially as developed into text, is clear, whereas terminology for a discussion of the production and interpretation of graphic expressions does not have a consensus on terms analogous to writing and reading. This essay uses the word “reading” for making sense of images as well as for the decipherment of letters and words, and “drawing” when marks do not constitute writing with semantic content. In the development of skills, writing is a modality of drawing. The case studies used highlight a range of factors that influence the reading of written/drawn work: the distinct visual quality of Robert Grenier’s “scrawl poems” and their relation to the page; the importance of page format in Ado Hamelryck’s book of indecipherable code; Fiona Banner’s “life writing” process and its outcome, text-as-drawing, a verbal portrait in a format similar to painting; and the communicative effect of Cy Twombly’s gestural inscriptions on paint background. These cases show that the orientation of making and viewing the work influences whether the work is seen as drawing or writing. The conclusion looks more closely at two aspects: firstly, a consideration of how drawings might be read is extended to bring in the notion of alternative literacies. Secondly, in terms of production of drawing, an important factor that distinguishes drawing from writing is an “invisible element that makes the work appear” – the surface.

Keywords: writing, drawing, reading, mark, surface

Cubism brought the word into the painting, Futurism recast it as typography, and, half a century later, as part of Conceptualism, language – usually painted or typeset words – became a fit subject for art. Since then, the affiliations and tensions between word and image have been manifest in various ways, some of which I will consider in this essay through consideration of the constituents of script and mark in the liminal area between overt text and unambiguous image.

Many genres lie between writing and graphic expression and include works that make the reader hover between reading and looking. Some consist of asemic writing (writing without semantic content) and some are encodings of various sorts, but not understandable generally. Categories include calligrams, ideograms, rebuses, pictographs, logograms, codes, graffiti, talismanic art – a profusion that calls for careful consideration of what to include in this essay. Almost irresistibly intriguing and entirely germane to this topic are the work of Xu Bing and Guo Wenda, using “nonsense” Chinese characters, and Arabic calligraphers like Rachid Koraichi, whose deeply personal “alphabet” of signs is informed by the mystic traditions of Sufism and its use of letters as signs and gestures, or Ali Omar Emes, whose inclusion of poetry and its sources encourages an intertextuality that unites the picture plane with larger discourses, drawing on Arabic traditions that link recitation of poetry with transcendentalism (Harney 2007, p208) – or even, to return to Western artists, the calligraphic poems of Brion Gysin, inspired by Japanese and Arabic calligraphy – or Timothy Ely’s cribriform writing, or Hanne Darboven’s accumulative “writings” using coded numbers. (Elsewhere I have written analytically about Darboven, and also about Portuguese visual poet Ana Hatherly and Italian calligrapher Massimo Pollelo: http://margaret-cooter.blogspot.com, 18 November, 14 November, 21 October respectively.)

This study will focus on works that are related to Western written forms and that use hand drawn marks or handwritten, rather than typographic, letters.This disallows text art and other uses of typography (a technological, rather than an art, process) and semiotext (use of language per se), as well as a discussion of the relation of text to social forces, for example in advertising or in conjunction with images, such as captions to newspaper photographs.

Calligraphy may come to mind as the prime example of the melding of writing and drawing, but it falls outside my remit, even though calligraphers such as Denise Lach and Thomas Ingmire have extended calligraphy’s scope from “fine communication” via text into an abstract textural mode in which the image regains independence from the word. I consider that, rather than occupying a space between image and text, calligraphy encompasses both, even when the rules of visual and verbal language are in opposition: though the calligraphic line draws the word, the visual aspect is subsumed in the more important purpose of legibility and readability. Although calligraphy is concerned with visual, verbal, semantic, referential, and historical dimensions (Ingmire 2001, p67), it seems to me that calligraphy is a transcription, rather than a reformulation.

Terms that describe production of and interaction with script and text are straightforward, but similar terms in regard to graphic expression are less clear-cut. “Reading” succinctly describes the process of visually examining and understanding text, but for images there is no consensus on a word analogous to “reading”. Deciphering, interpreting, perusing, scanning, studying, viewing, looking, picturing, seeing are candidates. For “writing”, possibilities for the equivalent term include drawing, representation, presentation, tracing, drafting – possibly even extraction. I will use “reading” to apply to looking at “pictures” as well as for the decipherment of letters and words, and “drawing” when marks do not constitute writing with semantic content.

Part of this difficulty in terminology, Tim Ingold points out (2007, p136) is that the Greek verb graphein (from which arose the plethora of words including -graph, referring to both text and images) meant “engrave, scratch” – and that distinguishing this reductive process from the process of adding flowing ink to a surface is echoed in the modern idea of writing as an act of composition separate from drawing. Ingold sets out four criteria by which writing may be distinguished: it is in a notation (a finite set of symbols); it is not an art (as drawing is); it is a technology; and it is linear (2007, p120) . Drawing combines observation and description in a single gestural movement (Ingold 2011, p222) and uses “an exploring line alert to changes of rhythm and feelings of surface and space” (Ingold 2007, quoting Andy Goldsworthy, p129).

As well as being used for major imaginative acts, both writing and drawing have been used for recording observations, and for communication – for example, architects’ use of drawing as a “shared and participatory tool of non-verbal exchange” has been extensively studied ( Petherbridge 2008, p33). As I will argue later, the general familiarity with making sense of text does not generally extend to reading drawings. Rawson (1979, p8) has said that drawing needs to be read with special care and sympathy because it projects inner images, and the artist’s deep involvement with those images. There are three main elements in reading a drawing, he says (1979, p14): “First there is the material support or surface – paper and so on. Second are the marks made upon it. Third is the image we grasp from combining the first two.”

It is evident that in a child’s development, speech precedes writing. Drawing is the intermediary between speech and writing, as children learn to form each letter, before combining them into words and sentences – units of utterance and meaning, used for communication. The 20 stages of development in children’s drawing identified by Kellogg were simplified by Golomb into two components: loops and circles, and parallel lines, generated respectively by children’s circular and linear arm and hand movements (Anning 2008, p94). Writing is itself a modality of drawing, says Ingold (2007, p147) and the two processes of enskilment are strictly inseparable; rules provide a scaffold for the learning process, but the capacity to write (and draw) emerges in and through the growth and development of the human being in his or her environment.

This brings us to a consideration of a range of factors that influence reading of work that falls in the liminal area between written and drawn, as shown in visual poetry of Robert Grenier, a book by Ado Hamelryck, Fiona Banner’s “life writing”, and the “blackboard paintings” of Cy Twombly. After this, I will focus on how drawings might be read, and on one of the factors important to the making and perception of drawing, the “invisible” surface.

Seeing precedes reading: Robert Grenier’s “scrawl poems”

Abstract: Many interesting and relevant examples non-Western examples of work that falls in an ambiguous area between drawing and writing exist, but those used in this study have been produced in Europe and America. Calligraphy seems an obvious example but falls outside this ambiguous area. The terminology to discuss writing, especially as developed into text, is clear, whereas terminology for a discussion of the production and interpretation of graphic expressions does not have a consensus on terms analogous to writing and reading. This essay uses the word “reading” for making sense of images as well as for the decipherment of letters and words, and “drawing” when marks do not constitute writing with semantic content. In the development of skills, writing is a modality of drawing. The case studies used highlight a range of factors that influence the reading of written/drawn work: the distinct visual quality of Robert Grenier’s “scrawl poems” and their relation to the page; the importance of page format in Ado Hamelryck’s book of indecipherable code; Fiona Banner’s “life writing” process and its outcome, text-as-drawing, a verbal portrait in a format similar to painting; and the communicative effect of Cy Twombly’s gestural inscriptions on paint background. These cases show that the orientation of making and viewing the work influences whether the work is seen as drawing or writing. The conclusion looks more closely at two aspects: firstly, a consideration of how drawings might be read is extended to bring in the notion of alternative literacies. Secondly, in terms of production of drawing, an important factor that distinguishes drawing from writing is an “invisible element that makes the work appear” – the surface.

Keywords: writing, drawing, reading, mark, surface

Cubism brought the word into the painting, Futurism recast it as typography, and, half a century later, as part of Conceptualism, language – usually painted or typeset words – became a fit subject for art. Since then, the affiliations and tensions between word and image have been manifest in various ways, some of which I will consider in this essay through consideration of the constituents of script and mark in the liminal area between overt text and unambiguous image.

Many genres lie between writing and graphic expression and include works that make the reader hover between reading and looking. Some consist of asemic writing (writing without semantic content) and some are encodings of various sorts, but not understandable generally. Categories include calligrams, ideograms, rebuses, pictographs, logograms, codes, graffiti, talismanic art – a profusion that calls for careful consideration of what to include in this essay. Almost irresistibly intriguing and entirely germane to this topic are the work of Xu Bing and Guo Wenda, using “nonsense” Chinese characters, and Arabic calligraphers like Rachid Koraichi, whose deeply personal “alphabet” of signs is informed by the mystic traditions of Sufism and its use of letters as signs and gestures, or Ali Omar Emes, whose inclusion of poetry and its sources encourages an intertextuality that unites the picture plane with larger discourses, drawing on Arabic traditions that link recitation of poetry with transcendentalism (Harney 2007, p208) – or even, to return to Western artists, the calligraphic poems of Brion Gysin, inspired by Japanese and Arabic calligraphy – or Timothy Ely’s cribriform writing, or Hanne Darboven’s accumulative “writings” using coded numbers. (Elsewhere I have written analytically about Darboven, and also about Portuguese visual poet Ana Hatherly and Italian calligrapher Massimo Pollelo: http://margaret-cooter.blogspot.com, 18 November, 14 November, 21 October respectively.)

This study will focus on works that are related to Western written forms and that use hand drawn marks or handwritten, rather than typographic, letters.This disallows text art and other uses of typography (a technological, rather than an art, process) and semiotext (use of language per se), as well as a discussion of the relation of text to social forces, for example in advertising or in conjunction with images, such as captions to newspaper photographs.

Calligraphy may come to mind as the prime example of the melding of writing and drawing, but it falls outside my remit, even though calligraphers such as Denise Lach and Thomas Ingmire have extended calligraphy’s scope from “fine communication” via text into an abstract textural mode in which the image regains independence from the word. I consider that, rather than occupying a space between image and text, calligraphy encompasses both, even when the rules of visual and verbal language are in opposition: though the calligraphic line draws the word, the visual aspect is subsumed in the more important purpose of legibility and readability. Although calligraphy is concerned with visual, verbal, semantic, referential, and historical dimensions (Ingmire 2001, p67), it seems to me that calligraphy is a transcription, rather than a reformulation.

Terms that describe production of and interaction with script and text are straightforward, but similar terms in regard to graphic expression are less clear-cut. “Reading” succinctly describes the process of visually examining and understanding text, but for images there is no consensus on a word analogous to “reading”. Deciphering, interpreting, perusing, scanning, studying, viewing, looking, picturing, seeing are candidates. For “writing”, possibilities for the equivalent term include drawing, representation, presentation, tracing, drafting – possibly even extraction. I will use “reading” to apply to looking at “pictures” as well as for the decipherment of letters and words, and “drawing” when marks do not constitute writing with semantic content.

Part of this difficulty in terminology, Tim Ingold points out (2007, p136) is that the Greek verb graphein (from which arose the plethora of words including -graph, referring to both text and images) meant “engrave, scratch” – and that distinguishing this reductive process from the process of adding flowing ink to a surface is echoed in the modern idea of writing as an act of composition separate from drawing. Ingold sets out four criteria by which writing may be distinguished: it is in a notation (a finite set of symbols); it is not an art (as drawing is); it is a technology; and it is linear (2007, p120) . Drawing combines observation and description in a single gestural movement (Ingold 2011, p222) and uses “an exploring line alert to changes of rhythm and feelings of surface and space” (Ingold 2007, quoting Andy Goldsworthy, p129).

As well as being used for major imaginative acts, both writing and drawing have been used for recording observations, and for communication – for example, architects’ use of drawing as a “shared and participatory tool of non-verbal exchange” has been extensively studied ( Petherbridge 2008, p33). As I will argue later, the general familiarity with making sense of text does not generally extend to reading drawings. Rawson (1979, p8) has said that drawing needs to be read with special care and sympathy because it projects inner images, and the artist’s deep involvement with those images. There are three main elements in reading a drawing, he says (1979, p14): “First there is the material support or surface – paper and so on. Second are the marks made upon it. Third is the image we grasp from combining the first two.”

It is evident that in a child’s development, speech precedes writing. Drawing is the intermediary between speech and writing, as children learn to form each letter, before combining them into words and sentences – units of utterance and meaning, used for communication. The 20 stages of development in children’s drawing identified by Kellogg were simplified by Golomb into two components: loops and circles, and parallel lines, generated respectively by children’s circular and linear arm and hand movements (Anning 2008, p94). Writing is itself a modality of drawing, says Ingold (2007, p147) and the two processes of enskilment are strictly inseparable; rules provide a scaffold for the learning process, but the capacity to write (and draw) emerges in and through the growth and development of the human being in his or her environment.

This brings us to a consideration of a range of factors that influence reading of work that falls in the liminal area between written and drawn, as shown in visual poetry of Robert Grenier, a book by Ado Hamelryck, Fiona Banner’s “life writing”, and the “blackboard paintings” of Cy Twombly. After this, I will focus on how drawings might be read, and on one of the factors important to the making and perception of drawing, the “invisible” surface.

Seeing precedes reading: Robert Grenier’s “scrawl poems”

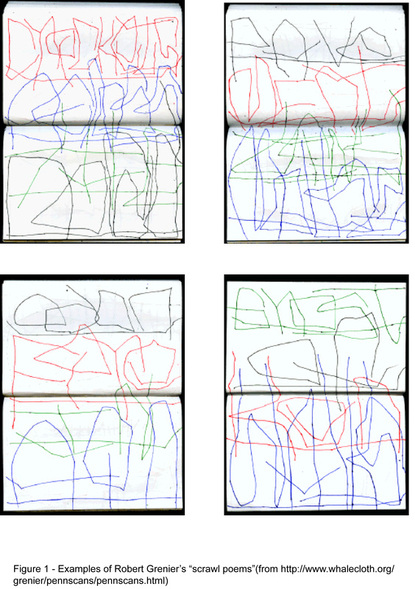

Robert Grenier’s short visual poems are concerned with how we actually “feel” language at the point of impulse, and are pointers to the psychological qualities of the mind that perceived them. They explore the "sixth sense" – wherein the imagination discovers mysterious connections between reality and “saved” referents, connections that were not apparent under normal syntactical practice, as the mind worked at organising data from ongoing reality (Faville 2007).

Since the 1980s Grenier rejected using type in favour of "drawn" poems – his “scrawl” poems (figure 1)– moving on to exploring a new formality: coloured-line designs of three and four words, written in notebooks and displayed framed on the wall. The layering of textures, via colour, helps reading (and communication); the poems’ richness comes from this reduction to shape and line, as well as the evocative nature of the sparse text. “The gestalt of the page as a whole,” says Drucker (1998, p133) “is textural rather than textual in character.” Their distinct visual quality highlights the writing process in the work’s final visual appearance on the page.

The sense of any of these poems is not its significance – hence they cannot be "translated" into typeface, or deciphered quickly enough (even by Grenier himself at times during his performances) to be read out loud, even though the space of the page limits the amount of linear elements. Each letter is expressed through the effort of its formation, and reading requires minute attention to form – the reader, in seeking to comprehend these unknown glyphs, must re-compose the words with almost as much effort as the author used. The space of the poem becomes an integral part of its meaning also in the confines of the page and the crowding of the words, further complicating decipherment.

These poems take understandable written language towards an extreme – the syntax makes deriving an exact meaning difficult (perhaps desirable in a poem), and the "drawing" conceals the letter forms, slowing down the semantic immediacy and making any "reading" into an obstacle course. There comes an instant when the word in the scrawl poem pops into consciousness – and the graphic format of these poems plays with making that moment explicit. Reading reveals a secret. The poems also play with the notion of the private and the public, with admission into a select circle. Certainly their fragmentary nature works as a metaphor for the fragmentation of our vision and perception (Davies 2008), and the form of the poem is part of its content.

Writing as a mark of seeing: Fiona Banner’s “life writing”

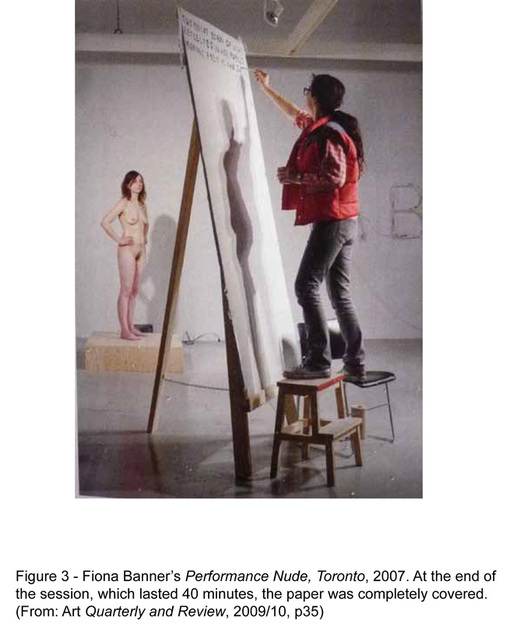

Fiona Banner’s “Performance Nude” (figure 2) evolved from her written descriptions of the on-screen action of war and pornography films. One of these, War Porn, she describes as “a big handwritten drawing, possibly not that legible (other than to me)” (Banner 2009, p11). She became increasingly involved in what she describes as "the intimate space between the characters” and went on to work with a striptease artist, describing her actions, and this work segued into the Performance Nudes. These are a riff on traditional life drawing (given that life drawing is the interaction of the artist's eye, mind, and gesture with the surface of the paper), the result of which, written with the support of an easel, was a surface filled with writing, describing the model – rather than a drawing (a depiction) sitting on a surface.

The series began in 2006 and ended in 2009 (Banner 2009), recording over 20 sittings and related works, some in front of live audiences – hence “performance”. Banner has called these subjective observational encounters as "life writings" and regards them not so much as the depiction of an individual person as a portrait of a complex and multi-layered encounter: "I was trying to represent that moment and all the failures and false starts of that moment," she says. Because the text is presented pictorially, “as an instant ... you scan [the texts] like pictures, so the narrative is kind of scrambled. They are neither writing, in the formal sense, or are they pictures. ... We’re so caught up in the visual world that we don’t really think of verbal encounters as portraits” (Banner 2009, p13).

The textual portraits are created in a manner resembling the processes that would be used in a traditional figurative drawing of the same model. The written engagement evidences the process of close observation and the creative decisions involved in making the work. Adjustments of artistic response call for adjustments to the direction and nuance of her thinking and hence of the (written) line. Further, they are made and displayed in the vertical orientation used for art, rather than horizontally like written text.

Format signals sense: Ado Hamelryck’s book

The series began in 2006 and ended in 2009 (Banner 2009), recording over 20 sittings and related works, some in front of live audiences – hence “performance”. Banner has called these subjective observational encounters as "life writings" and regards them not so much as the depiction of an individual person as a portrait of a complex and multi-layered encounter: "I was trying to represent that moment and all the failures and false starts of that moment," she says. Because the text is presented pictorially, “as an instant ... you scan [the texts] like pictures, so the narrative is kind of scrambled. They are neither writing, in the formal sense, or are they pictures. ... We’re so caught up in the visual world that we don’t really think of verbal encounters as portraits” (Banner 2009, p13).

The textual portraits are created in a manner resembling the processes that would be used in a traditional figurative drawing of the same model. The written engagement evidences the process of close observation and the creative decisions involved in making the work. Adjustments of artistic response call for adjustments to the direction and nuance of her thinking and hence of the (written) line. Further, they are made and displayed in the vertical orientation used for art, rather than horizontally like written text.

Format signals sense: Ado Hamelryck’s book

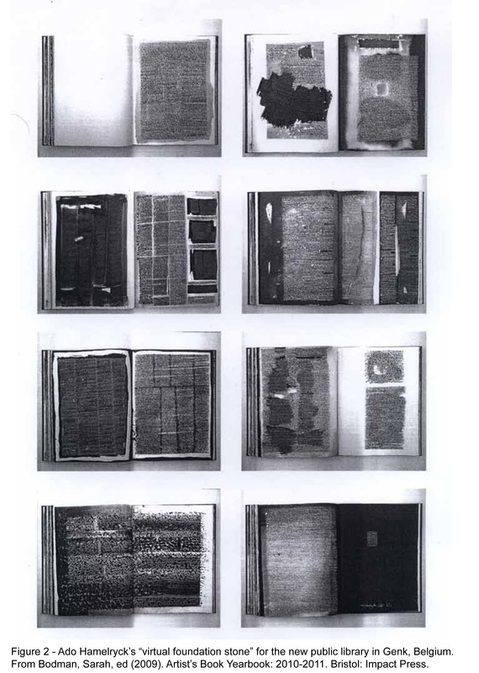

“Handwriting,” said Heller and Ilic (2006, p59), “dislodges pretentions and alters perception of what the printed page should be” – and in Belgian artist Ado Hamelryck’s book the marks are perceived in the context of their presentation as a series of linked pages; although illegible, they become a text. The book was given to the artist as the “virtual foundation stone” for the new library of the city of Genk, Belgium; filled during the years of library construction, in 2008 it became the first book the library purchased. This modern object acts as a historical marker and draws on a long tradition relevant to its destination.

The book (figure 3) is painstakingly handwritten, and imbued with the personality of the maker; it contains over 200 pages, and provides much variation, yet through its materiality it is a unified object. Close up, the writing – in graphite or ink – looks like some sort of personal code; the uninitiated cannot “read” it for meaning. Yet the page margins and blocks and columns of text on the integrated pages signal that it is meant to be read. The pages that consist of many columns resemble magazine pages; often there seems to be space for an illustration, as solid (inked) ground replaces the symbolic marks. Sometimes the background breaks away from the rectangular shape, and the background emphasises the fact that the text is overlaid on a surface. In this work, the act of "writing" becomes a code for participation in literate (or even scholarly) culture - but the "nonsense" of the result would dismay a reader looking for information and meaning. The vacuum of meaning in the asemic writing must be filled in by the reader. “My 'writing' has no literary content,” Hamelryck says; “It has no narrative or decorative value. It's just what it is.”

To someone who can "read art", the book communicates many meanings or resonances – palimpsest, artefact, parody, aesthetic object. Its references are to the whole history and panoply of written and printed books. As a book, it is meant to be handled like any other book – it was written and can be read flat on a table. Many aspects of its “reading” relate to its appearance as a book object: the spatial dimension of the page is a feature of visual organization not normally used by writing (Drucker 1998, p86), and structures specific to the book, such as gutters, are part of their metalanguage (1998, p171). Drucker also points out that the visual performance on the page is a structurally logical and meaningful schema (1998, p103). Such spatial features have no verbal analogue – it is up to artists to make us conscious of what we do not usually study and talk about in words.

Lyrical graffiti? Cy Twombly’s “blackboard paintings”

The book (figure 3) is painstakingly handwritten, and imbued with the personality of the maker; it contains over 200 pages, and provides much variation, yet through its materiality it is a unified object. Close up, the writing – in graphite or ink – looks like some sort of personal code; the uninitiated cannot “read” it for meaning. Yet the page margins and blocks and columns of text on the integrated pages signal that it is meant to be read. The pages that consist of many columns resemble magazine pages; often there seems to be space for an illustration, as solid (inked) ground replaces the symbolic marks. Sometimes the background breaks away from the rectangular shape, and the background emphasises the fact that the text is overlaid on a surface. In this work, the act of "writing" becomes a code for participation in literate (or even scholarly) culture - but the "nonsense" of the result would dismay a reader looking for information and meaning. The vacuum of meaning in the asemic writing must be filled in by the reader. “My 'writing' has no literary content,” Hamelryck says; “It has no narrative or decorative value. It's just what it is.”

To someone who can "read art", the book communicates many meanings or resonances – palimpsest, artefact, parody, aesthetic object. Its references are to the whole history and panoply of written and printed books. As a book, it is meant to be handled like any other book – it was written and can be read flat on a table. Many aspects of its “reading” relate to its appearance as a book object: the spatial dimension of the page is a feature of visual organization not normally used by writing (Drucker 1998, p86), and structures specific to the book, such as gutters, are part of their metalanguage (1998, p171). Drucker also points out that the visual performance on the page is a structurally logical and meaningful schema (1998, p103). Such spatial features have no verbal analogue – it is up to artists to make us conscious of what we do not usually study and talk about in words.

Lyrical graffiti? Cy Twombly’s “blackboard paintings”

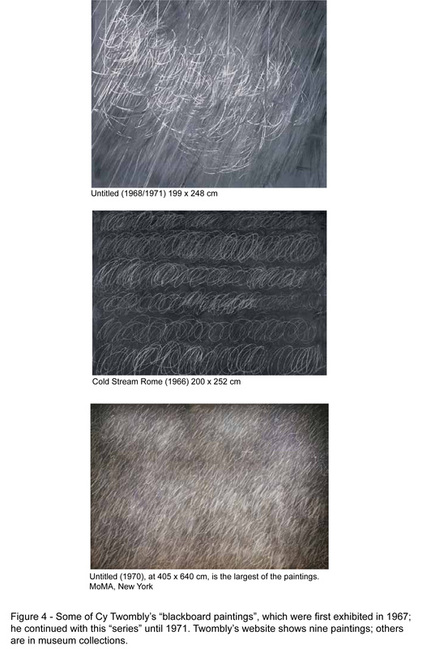

Words, fragmented into almost indecipherable letters – hints of classical allusions – are sprinkled throughout Cy Twombly's work, but it is in the "blackboard paintings" (figure 4) that his "writing", or rather scribble, is most gestural. The label of blackboard paintings derives from the grey, painted background, with its lighter areas resembling erasure. The large linear marks (usually made in wax crayon – a drawing suspended within the liquid medium of paint) evoke a proto-text, "something almost being said".

Some of the works in the series use just one form of mark, amplifying it; others play off several kinds of line with each other. The paintings operate in a language that only some of the viewers speak: some elements are recognisable and categorisable; but even without writing a recognisable language, they act to evoke mysteries and emotion.

The repeated looped elements resemble handwriting exercises, yet making the paintings is an unpredetermined process not aiming for any particular outcome, and the viewer's experience is not about any particular mark or line, but about the repetition of the process and the accumulation of lines. Within the gesture of the loop, the effect of layering seems almost random, yet it is this process that generates the complexity of the painting, balancing order and disorder, randomness and control. The accumulation of lines flattens the field of the canvas, not offering a focal point. Even so, the drawing-as-handwriting makes the large canvas into an intimate and personal space, the intimate scribble skillfully scaled up.

The physical release of energy from the body speaks about nothing, but communicates a tremendous amount. The fluid line, the ductus,is a visible action, liberated from the dictates of material; Barthes (1985) wrote that "however supple, light or uncertain it may be, [it] always refers to a force, to a direction; it is an energon, a labor which reveals – which makes legible – the trace of its pulsion and its expenditure." According to Rosalind Krauss, it is the ductus – the performative language of direction, sequencing, and speed of writing – that is dominant in Twombley’s work (Van Alphen 2008, p65 ).

Twombly's large paintings have been compared to graffiti; on this topic he said: "Graffiti is linear and it's done with a pencil, and it's like writing on walls. But [in my paintings] it's more lyrical ... it's graffiti but it's something else, too. ... Graffiti is usually a protest – ink on walls – or has a reason for being naughty or aggressive" (Serota 2008).

Marking and reading

Defining what drawing is is what makes it difficult as a subject of study, says Petherbridge (2008, p27). Other manifestations of art have been clearly named and niched, but drawing “is slippery and irresolute in its fluid status as performative act and idea; as sign, and symbol and signifier; as conceptual diagram as well as medium and process and technique” (2008, p27). Drawings have been regarded as “temporary” objects, a stage in the making of paintings or buildings or sculptures, and in the past century the skill of drawing has been devalued, along with its capacity for teaching us how to look. This has repercussions for our reading of drawn works.

In reading both text and images, the viewer looks to find a pattern, a significance. The work triggers a response, and the reader discerns information or meaning - the writer or artist’s intention becomes manifest in the work’s reception. To read a text the reader has to learn to recognize the clues that indicate how texts are to be taken, and in writing they must learn to bring these very devices under deliberate control (Olson 1994, p253). Thus the job of artist and writer alike is to communicate their intention, and nothing beside. Arguably this is less difficult with text, for not only has text been privileged over images ever since Lessing claimed, more than two centuries ago, that the abstract signs of language gave it greater freedom and expressivity than the natural signs of visual art, but literature has evolved a corpus of philosophically-based “reader response” theories, which art theory is still catching up with (Poetry Beyond Text [2011]).

Furthermore, text is a more democratic medium than the painted or drawn image, in Western culture at least, for literacy is nearly universal; whereas being able to “read art” is part of the cultural capital of a subgroup, and might even – especially when graphic thinking is de-emphasised in the education system – be seen as a marginal activity. Even as handwriting, replaced by keyboarding for everyday purposes, becomes something unusual to be used for special purposes, drawing has been sidelined to the uncommon activity of visual exploration, a kind of communicating with oneself. Learning to read the meanings of marks, building up an inner fund of forms that access a different level of thought and communicate non-verbal feelings – these are rarified activities akin to cryptography.

Being able to read drawings could be considered as an alternative literacy. Roberts et al (2007, p20) state that cultures throughout the world contain many more modalities of literacy than those restricted to alphabets; some are visual and others tactile and performance-based. They say that “illiterate” cultures invented and used highly complex systems of graphic communication, and that literacy should be considered along two parallel axes within a given culture: “production, or the process of inscription, and response, or how an encoded message is received and understood. Levels of ability both as inscriber and as receiver can shift within an individual lifetime, but also scribal traditions can change over time in response to social and political transformations.” Writing is more than a record of language; it contains a set of assumptions shared by “literate” people – whether literate in terms of text, or in terms of graphic representation.

Surface and space

Rawson mentioned “the material support or surface” as one of the main elements in reading a drawing (1979, p14) – it is there to receive the traces of the artist’s activity. The support is one of “the elements that become invisible in making the work appear”, as Wolfreys (2004, p84) puts it in describing Derrida’s writings on art: “inscription that ... being largely unread, makes possible the signification of the work of art as art.” Traces, brush strokes, pencil lines, traces – and words – are all projections and supports, movements and elements in a structure allowing for representation, but at the same time these marks perform the representation and require the support of canvas or paper or page.

In painting, the work must fill the frame – its solid medium covers the surface – but drawing is not compelled to observe this “law of the all-over”: the blank surface of the paper does not have to be conceived as a surface in the way the canvas does – as an area that needs to be filled. The drawn line “can unfold in a way that responds to its immediate spatial and temporal milieu, having regard for its own continuation rather than for the totality of the composition” (Ingold 2011, p222).

We automatically refer marks drawn on a sheet of paper to its edges, even though we may not be conscious of doing so, says Rawson (1979, p15); the space of the drawing surface forms part of the image, and the image is placed in relation to the drawing-plane. That drawing-plane is, like the painting-plane, often vertical, both in the making of the work (on an easel) and in the conditions that allow for reading of the work (on a wall). The writing-plane, though, is almost always horizontal – on paper laid on a table, or in a book lying horizontally, and when being read it is usually held in the hand, making an intimate and private reading space – though Drucker (1998, p88) is tempted to claim the act of reading as public, in contrast to the private act of writing. Presenting art –paintings or prints especially – to its “readers” usually involves public display on a wall, though prints or even drawings might be presented in portfolios for individual interaction, and sketchbooks when shown are tantalizingly laid open to just one page, spread under glass, preserving their privacy. Artists’ books – the fusion of text and/or image and the space(s) of the page(s) – again occupy the horizontal rather than the vertical; though their reading involves personal interaction with a defined sequence of pages, the opportunity for such interaction is not always available. One-off publications are, through their format, on a par with the recognised uniqueness of the sketchbook in terms of presentation.

My awareness of the significance of the surface has emerged only in the final stages of writing this essay, and I will be going on to look more closely at perceptions, qualities, and conceptual formulations of the surface (and perhaps come to understand Derrida’s “subjectile”). Ingold, whose work on lines has been crucial for my thinking about my project, speaks of movement along a path of observation. This “travelling along the surface” corresponds to another surface important to my project, the surface over which the vehicle in which I sit to “write” my lines travels. I chose the essay topic because I was unclear whether the lines that I make on bus and tube journeys are writing or drawing, and it is satisfying that my path of discovery has brought this underlying concept into view.

Bibliography

Anning, Angela (2008). Reapprasing young children’s mark-making and drawing. In: Garner, Steve, ed. Writing on drawing: essays on drawing practice and research. Bristol: Intellect, pp93-108.

Banner, Fiona (2009). Performance nude. London: Other Criteria.

Barthes, Roland (1985). Cy Twombly: works on paper; reprinted in The responsibility of forms: critical essays on music, art and representation. Trans. Richard Howard. Oxford: Blackwell.

Davies, James (2008). Review: Robert Grenier – 64 (The Irony of Flatness, Bury Art Gallery, 19 July – 8 November). Parameter Magazine September 2008. http://www.parametermagazine.org/grenier.htm (accessed 21 November 2011)

Depoorter, Matthis (2011). Ado Hamelryck: ‘In der beginner war es zwart’ (interview). Kunst in Limburg, April. http://www.kunstinlimburg.be/kunststukken/ado-hamelryck-den-beginne-was-er-zwart-interview (accessed 24 November 2011)

Smeets, Rudi (2009). 'Zwart is de meest sprekende kleur' [Interview with Ado Hamelryck].De Standaard, 11 May. http://www.standaard.be/artikel/detail.aspx?artikelid=792A2QQU (accessed 24 November 2011)

Drucker, Joanna (1998). Figuring the word: essays on books, writing, and visual poetics. New York: Granary.

Faville, Curtis (2007). Stone cutting all the way. Jacket vol 34, October. http://jacketmagazine.com/34/faville-saroyan-grenier.shtml (accessed 21 November 2011)

Filreis, Al (2010). Robert Grenier: drawing poem-images. January 13. http://jacket2.org/commentary/robert-grenier (accessed 21 November 2011)

Hamelryck, Ado (2006). Interview in Isel magazine, cited at http://www.uitingenk.be/nl/uig_content/record/3225/ado-hamelryck.html (accessed 24 November 2011)

Harney, Elizabeth (2007). Word play: text and image in contemporary African arts. In: Kreamer, Christine M et al, eds. Inscribing meaning: writing and graphic systems in African art. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp201-226.

Heller, Steven and Ilic, Mirko (2006). Handwritten: expressive lettering in the digital age. London: Thames & Hudson.

Ingmire, Thomas (2001). The space of writing. In: Timothy Wilcox, ed. Spring lines: contemporary calligraphy from east and west. Ditchling: Edward Johnston Foundation, pp65-75.

Ingold, Tim (2007). Lines: a brief history. London: Routledge.

--- (2011) Being alive: essays on movement, knowledge and description. London: Routledge.

Dixon Hunt John; Lomas, David, and Michael Corris, Michael, eds (2009). Art, word and image: 2,000 years of visual/textual interaction. London: Reaktion Books.

Olson, David R (1994). The world on paper: the conceptual and cognitivie implications of writing and reading. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Petherbridge, Deanna (2008). Nailing the luminal: the difficulties of defining drawing. In: Garner, Steve, ed. Writing on drawing: essays on drawing practice and research. Bristol: Intellect, pp27-41.

---- (2010). The primacy of drawing: histories and theories of practice. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Poetry Beyond Text ([2011]). http://www.poetrybeyondtext.org/literary-criticism.html (accessed 28 November 2011).

Raskin, Ludo (2008). Ado Hamelryck [review of exhibition at CIAP, Hasselt, Belgium]. http://ciap.be/?p=207 (accessed 24 November 2011)

Rawson, Philip (1979). Seeing through drawing. London: BBC.

Roberts, Mary Nooter et al (2007). Inscribing meaning: ways of knowing. In: Kreamer, Christine M et al, eds. Inscribing meaning: writing and graphic systems in African art. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp13-27.

Rogers, Henry (2005). Writing systems: a linguistic approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Serota, Nicholas (2008) ‘I work in waves' [interview with Cy Twombly]. The Guardian, 3 June 2008. http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/jun/03/art1 (accessed 26 November 2011) Van Alphen, Ernst (2008). Looking at drawing: theoretical distinctions and their usefulness. In: Garner, Steve, ed. Writing on drawing: essays on drawing practice and research. Bristol: Intellect, pp60-70.

Wolfreys, Julian (2004). Art. In: Reynolds, Jack and Roffe, Jonathan, eds. Understanding Derrida. New York, London: Continuum.